The Wrangler is without doubt the most popular 4WD within our community, with recent overland-ready offerings such as this 2005, 2015 w/ Ursa Minor, and 2021 w/ Xtreme Recon Package. It’s sold factory equipped with a heavy-duty 4WD system, Dana solid axles, front and rear lockers, off-road tuned suspension, and more. In addition, it enjoys unparalleled aftermarket support, so whether you’re looking to build a dedicated rock crawler or an around-the-world micro camper, you can make it happen. Subsequently, no two are the same, as demonstrated by inspiring builds from Justin B McBride, Burn the Map Adventures, and Casey 250. Cue today’s 2005 Jeep Wrangler Unlimited Rubicon (22,000 miles since engine swap), which boasts a GM 5.3-liter V8 Iron Block engine conversion and a plethora of premium aftermarket upgrades. Learn more by listening to Building the LJ and TJ Jeep Wrangler for Overlanding on the Overland Journal Podcast.

From the Seller:

From the Seller:

“This vehicle is set up for a more technical and aggressive portfolio of trails. I designed the drawer/deck system to provide an overly generous amount of multi-lockable storage, but also to allow robust aircraft-track-style mounting points for your additional overlanding kit. Similarly, I designed and cut the overhead console for switches and the radios to keep them as high as possible in case your water crossing is a little deeper than you expected. Shortly after I purchased it from my friend (the original builder) at the start of Covid 19, my family situation changed. I have not been able to use it for its intended purpose and only drive it enough to keep the gas fresh.”

2005 Jeep Wrangler Unlimited Rubicon

2005 Jeep Wrangler Unlimited Rubicon

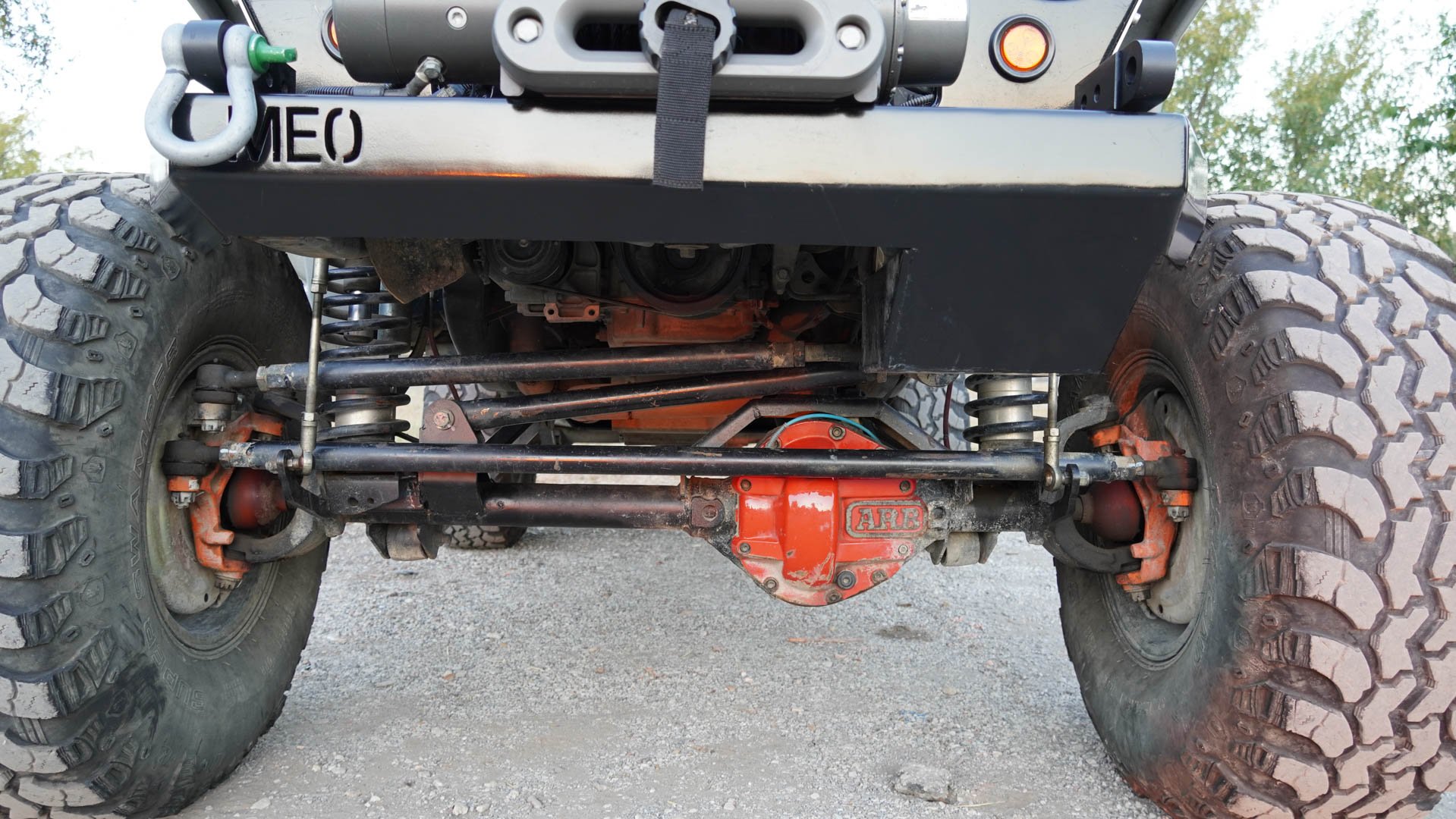

The Wrangler is fitted with a GM 5.3-liter iron block that, from the factory, produces between 310-320 horsepower and 335-383 pound-feet of torque. A powerful V8 motor is matched with impressive capability thanks to 4WD, high and low range, a lifted and uprated suspension, armor, front and rear ARB lockers, Dana axles, and Warn manual locking hubs. Inside, these rugged attributes are balanced with driver comforts that include:

- Corbeau seats

- Aftermarket stereo

- Lockable center console

- CB radio

- Power steering

Distinguishing Features

Distinguishing Features

- Clayton 5.5 Competition suspension

- ATX Series wheels with Irok ND tires

- MEO front winch bumper with Warn 9000i and ARB rear bumper with swing arm

- Custom 48-inch full extension drawers on AccuRide heavy-duty slides

- GenRight full cage

- ARB twin air compressor

- GenRight aluminum fenders

This 2005 Jeep Wrangler Unlimited Rubicon is listed for $32,000 and is currently located in Austin, Texas. Check the full vehicle specifications via the original Expedition Portal forum post here.

This 2005 Jeep Wrangler Unlimited Rubicon is listed for $32,000 and is currently located in Austin, Texas. Check the full vehicle specifications via the original Expedition Portal forum post here.

Our No Compromise Clause: We do not accept advertorial content or allow advertising to influence our coverage, and our contributors are guaranteed editorial independence. Overland International may earn a small commission from affiliate links included in this article. We appreciate your support.